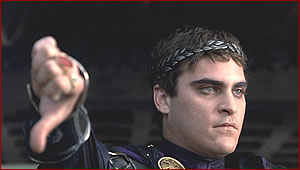

Some application and assessment processes are for limited goods, and some are for unlimited goods, and it’s important to understand the difference. PhD vivas and driving tests are assessments for unlimited goods – there’s no limit on how many PhDs or driving licenses can be issued. In principle, everyone could have one if they met the requirements. You’re not going to fail your driving test because there are better drivers than you. Other processes are for limited goods – there is (usually) only one job vacancy that you’re all competing for, only so many papers that a top journal accept, and only so much grant money available.

You’d think this was a fairly obvious point to make. But talking to researchers who have been unsuccessful with a particular application, there’s sometimes more than a hint of hurt in their voices as they discuss it, and talk in terms of their research being rejected, or not being judged good enough. They end up taking it rather personally. And given the amount of time and effort that must researchers put into their applications, that’s not surprising.

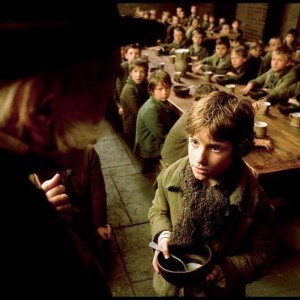

It reminds me of an unsuccessful job applicant whose opening gambit at a feedback meeting was to ask me why I didn’t think that she was good enough to do the job. Well, my answer was that I was very confident that she could do the job, it’s just that there was someone more qualified and only one post to fill. In this case, the unsuccessful applicant was simply unlucky – an exceptional applicant was offered the job, and nothing she could have said or done (short of assassination) would have made much difference. While I couldn’t give the applicant the job she wanted or make the disappointment go away, I could at least pass on the panel’s unanimous verdict on her appointability. My impression was that this restored some lost confidence, and did something to salve the hurt and disappointment. You did the best that you could. With better luck you’ll get the next one.

Of course, with grant applications, the chances are that you won’t get to speak to the chair of the panel who will explain the decision. You’ll either get a letter with the decision and something about how oversubscribed the scheme was and how hard the decisions were, which might or might not be true. Your application might have missed out by a fraction, or been one of the first into the discard pile.

Some funders, like the ESRC, will pass on anonymised referees’ comments, but oddly, this isn’t always constructive and can even damage confidence in the quality of the peer review process. In my experience, every batch of referees’ comments will contain at least one weird, wrong-headed, careless, or downright bizarre comment, and sometimes several. Perhaps a claim about the current state of knowledge that’s just plain wrong, a misunderstanding that can only come from not reading the application properly, and/or criticising it on the spurious grounds of not being the project that they would have done. These apples are fine as far as they go, but they should really taste of oranges. I like oranges.

Don’t get me wrong – most referees’ reports that I see are careful, conscientious, and insightful, but it’s those misconceived criticisms that unsuccessful applicants will remember. Even ahead of the valid ones. And sometimes they will conclude that its those wrong criticisms that are the reason for not getting funded. Everything else was positive, so that one negative review must be the reason, yes? Well, maybe not. It’s also possible that that bizarre comment was discounted by the panel too, and the reason that your project wasn’t funded was simply that the money ran out before they reached your project. But we don’t know. I really, really, really want to believe that that’s the case when referees write that a project is “too expensive” without explaining how or why. I hope the panel read our carefully constructed budget and our detailed justification for resources and treat that comment with the fECing contempt that it deserves.

Fortunately, the ESRC have announced changes to procedures which allow not only a right of reply to referees, but also to communicate the final grade awarded. This should give a much stronger indication of whether it was a near miss or miles off. Of course, the news that an application was miles off the required standard may come gifted wrapped with sanctions. So it’s not all good news.

But this is where we should be heading with feedback. Funders shouldn’t be shy about saying that the application was a no-hoper, and they should be giving as much detail as possible. Not so long ago, I was copied into a lovely rejection letter, if there’s any such thing. It passed on comments, included some platitudes, but also told the applicant what the overall ranking was (very close, but no cigar) and how many applications there were (many more than the team expected). Now at least one of the comments was surprising, but we know the application was taken seriously and given a thorough review. And that’s something….

So… in conclusion…. just because your project wasn’t funded doesn’t (necessarily) mean that it wasn’t fundable. And don’t take it personally. It’s not personal. Just the business of research funding.

The new calendar year is traditionally a time for reflection and for resolutions, but in a fit of hubris I’ve put together a list of resolutions I’d like to see for the sector, research funders, and university culture in general. In short, for everyone but me. But to show willing, I’ll join in too.

The new calendar year is traditionally a time for reflection and for resolutions, but in a fit of hubris I’ve put together a list of resolutions I’d like to see for the sector, research funders, and university culture in general. In short, for everyone but me. But to show willing, I’ll join in too.