This week I was asked to be involved in a Research Grant application ‘bootcamp’ to talk in particular about the use of social media in pathways to impact plans, and academic blogging in general. I was quick to disclaim expertise in this area – I’ve been blogging for a while now, but I’m not an academic and I’m certainly not an expert on social media. I’m also not sure about this use of the word ‘bootcamp’. We already have ‘workshop’ and ‘surgery’ as workplace-based metaphors for types of activity, and I’m not sure we’re ready for ‘bootcamp’. So unless the event turns out to involve buzzcuts, a ten mile run, and an assault course, I’ll be asking for my money back.

But I thought I’d try to put together a list of resources and examples that I was already aware of in time for the session, and I then I wondered about ‘crowdsourcing’ (i.e. lazily ask my readers/twitter followers) some others that I might have missed. Hopefully we’ll then end up with a general list of resources that everyone can use. I’ve pasted some links below, along with a few observations of my own. Please do chip in with your thoughts, experiences, tips, and recommendations for resources.

———————————–

Things I have learnt about using social media

Blogging

- You must have a clear idea about your intended audience and what you hope to achieve. Blogging for the sake of it or because it’s flavour of the month or because you think it is expected is unlikely to be sustainable or to achieve the desired results.

- A good way to start is to search for people doing a similar thing and contact them asking if you can link to their blog. Everyone likes being linked to, and this is a good way to start conversations. Once established, support others in the same way.

- You have to build something of a track record of posts and tweets to be credible as a consistent source of quality content – you’ve got to earn a following, and this takes time, work, and patience. And even then, might not work. Consider a ‘soft launch’ to build your track record, and then a second wave of more intensive effort to get noticed.

- Posting quality comments on other people’s blogs, either in their comments section, or in a post on your blog, can be a good way to attract attention.

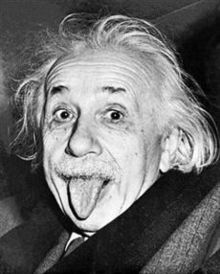

- Illustrate blog posts with a picture (perhaps found through google images) – a lot of successful bloggers seem to do this.

- Multi-author blogs and/or guest posts are a good way to share the load.

- And consequently, offering guest posts or content to established blogs is a way to get noticed.

- The underlying technology is now very straightforward. Anyone who is reasonably computer literate will have little trouble learning the technical skills. The editing frame where I’m writing this in looks a lot like Word, and I’ve used precisely no programming/HTML stuff – that can all be automated now.

- The technology of @s and # is fairly straightforward to pick up – find some relevant/interesting people to follow and you’ll soon pick it up, or read one of the guides below.

- A good way to reach people is to get “retweets” – essentially when someone else with a bigger following forwards your message. You do this by addressing posts to them using the @ symbol

- Generally the pattern of retweets seems to be when people find something interesting and it suits their message. So… the ESRC retweeted my blog post linking to their regional visit presentation when my blog post said nice things about the visit and linked to their presentation

- Weird mix of personal and professional. Some twitter accounts are uniquely professional, others uniquely personal, but many seem a mixture. Some of the usual barriers seem not to apply, or apply only loosely. Care needs to be taken here.

General

- Social media is potentially a huge time sink – keep in mind costs in time versus benefits gained

- It can be a struggle if you’re naturally shy and attention seeking doesn’t come easily to you

Resources and further reading:

Examples of individual UoN blogs:

Patter – Pat Thomson, School of Education http://patthomson.wordpress.com/

Political Apparitions – Steven Fielding, School of Politics http://stevenfielding.com/

Registrarism – Paul Greatrix, University Registrar http://registrarism.wordpress.com/

Cash for Questions, Adam Golberg, NUBS https://socialscienceresearchfunding.co.uk/

UoN Group/institutional/project blogs:

Bullets and Ballots – UoN School of Politics: http://nottspolitics.org/

China Policy Institute http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/chinapolicyinstitute/

Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility

http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/betterbusiness/

UoN blogs home http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/

Guides:

Twitter Guide – LSE Impact in Social Sciences

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2011/09/29/twitter-guide/

6 tips on blogging about research (Sarah Stewart (EdD Student, Otago University, NZ)

http://sarah-stewart.blogspot.co.uk/2012/04/my-top-6-tips-for-how-to-blog-about.html

Blogging about your research – first steps (University of Warwick)

http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/services/library/researchexchange/topics/gd0007/

Is blogging or tweeting about research papers worth it? (Melissa Terras, UCL)

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2012/04/19/blog-tweeting-papers-worth-it/

A gentle introduction to twitter for the apprehensive academic, (Dorothy Bishop, University of Oxford)

http://deevybee.blogspot.co.uk/2011/06/gentle-introduction-to-twitter-for.html

Twitter accounts:

List of official University of Nottingham Twitter accounts

https://twitter.com/#!/UniofNottingham/uontwitteraccounts

Lists of academic twitter accounts (Curator: LSE Impact project team)

https://twitter.com/#!/LSEImpactBlog/soc-sci-academic-tweeters

https://twitter.com/#!/LSEImpactBlog/business-tweeters

https://twitter.com/#!/LSEImpactBlog/arts-academic-tweeters

https://twitter.com/#!/LSEImpactBlog/think-tanks

——————

Some of the links and choices of examples, are more than a little University of Nottingham-centric, but then this was an internal event. I’ve not checked with the authors of the various resources I’ve linked to, and taken the liberty of assuming that they won’t mind the link and recognition. But happy to remove any on request.

Any resources I’ve missed? Any more thoughts and suggestions? Please comment below….

The new calendar year is traditionally a time for reflection and for resolutions, but in a fit of hubris I’ve put together a list of resolutions I’d like to see for the sector, research funders, and university culture in general. In short, for everyone but me. But to show willing, I’ll join in too.

The new calendar year is traditionally a time for reflection and for resolutions, but in a fit of hubris I’ve put together a list of resolutions I’d like to see for the sector, research funders, and university culture in general. In short, for everyone but me. But to show willing, I’ll join in too.