A version of this article first appeared in Funding Insight in July 2019 and is reproduced with kind permission of Research Professional. For more articles like this, visit www.researchprofessional.com

You’re applying for UK research council funding and suddenly you’re confronted with massive overhead costs. Adam Golberg tries to explain what you need to know.

Trying to explain Full Economic Costing is not straightforward. For current purposes, I’ll be assuming that you’re an academic applying for UK Research Council funding; that you want to know enough to understand your budget; and that you don’t really want to know much more than that.

If you do already know a lot about costing or research finances, be warned – this article contains simplifications, generalisations, and omissions, and you may not like it.

What are Full Economic Costs, and why are they taking up so much of my budget?

Full Economic Costs (fEC) are paid as part of UK Research and Innovation grants to cover a fair share of the wider costs of running the university – the infrastructure that supports your research. There are a few different cost categories, but you don’t need to worry about the distinctions.

Every UK university calculates its own overhead rates using a common methodology. I’m not going to try to explain how this works, because (a) I don’t know; and (b) you don’t need to know. Most other research funders (charities, EU funders, industry) do not pay fEC for most of their schemes. However, qualifying peer-reviewed charity funding does attract a hidden overhead of around 19% through QR funding (the same source as REF funding). But it’s so well hidden that a lot of people don’t know about it. And that’s not important right now.

How does fEC work?

In effect, this methodology produces a flat daily overhead rate to be charged relative to academic time on your project. This rate is the same for the time of the most senior professor and the earliest of early career researchers.

One effect of this is to make postdoc researchers seem proportionally more expensive. Senior academics are more expensive because of higher employment costs (salary etc), but the overheads generated by both will be the same. Don’t be surprised if the overheads generated by a full time researcher are greater than her employment costs.

All fEC costs are calculated at today’s rates. Inflation and increments will be added later to the final award value.

Do we have to charge fEC overheads?

Yes. This is a methodology that all universities use to make sure that research is funded properly, and there are good arguments for not undercutting each other. Rest assured that everyone – including your competitors– are playing by the same rules and end up with broadly comparable rates. Reviewers are not going to be shocked by your overhead costs compared to rival bids. Your university is not shooting itself (or you) in the foot.

There are fairness reasons not to waive overheads. The point of Research Councils is to fund the best individual research proposals regardless of the university they come from, while the REF (through QR) funds for broad, sustained research excellence based on historical performance. If we start waiving overheads, wealthier universities will have an unfair advantage as they can waive while others drown.

Further, the budget allocations set by funders are decided with fEC overheads in mind. They’re expecting overhead costs. If your project is too expensive for the call, the problem is with your proposal, not with overheads. Either it contains activities that shouldn’t be there, or there’s a problem with the scope and scale of what you propose.

However, there are (major) funding calls where “evidence of institutional commitment” is expected. This could include a waiver of some overheads, but more likely it will be contributions in kind – some free academic staff time, a PhD studentship, new facilities, a separate funding stream for related work. Different universities have different policies on co-funding and it probably won’t hurt to ask. But ask early (because approval is likely to be complex) and have an idea of what you want.

What’s this 80% business?

This is where things get unnecessarily complicated. Costs are calculated at 100% fEC but paid by the research councils at 80%. This leaves the remaining 20% of costs to be covered by the university. Fortunately, there’s enough money from overheads to cover the missing 20% of direct costs. However, if you have a lot of non-pay costs and relatively little academic staff time, check with your costings team that the project is still affordable.

Why 80%? In around 2005 it was deemed ‘affordable’ – a compromise figure intended to make a significant contribution to university costs but without breaking the bank. Again, you don’t need to worry about any of this.

Can I game the fEC system, and if so, how?

Academic time is what drives overheads, so reducing academic time reduces overheads. One way to do this is to think about whether you really need as much researcher time on the project. If you really need to save money, could contracts finish earlier or start later in the project?

Note that non-academic time (project administrators, managers, technicians) does not attract overheads, and so are good value for money under this system. If some of the tasks you’d like your research associate to do are project management/administration tasks, your budget will go further if you cost in administrative time instead.

However, if your final application has unrealistically low amounts of academic time and/or costs in administrators to do researcher roles, the panel will conclude that either (a) you don’t understand the resource implications of your own proposal; or (b) a lack of resources means the project risks being unable to achieve its stated aims. Either way, it won’t be funded. Funding panels are especially alert for ‘salami projects’ which include lots of individual co-investigators for thin slivers of time in which the programme of research cannot possibly be completed. Or for undercooked projects which put too much of a burden on not enough postdoc researcher time. As mentioned earlier, if the project is too big for the call budget, the problem is with your project.

The best way to game fEC it is not to worry about it. If you have support with your research costings, you’ll be working with someone who can cost your application and advise you on where and how it can be tweaked and what costs are eligible. That’s their job – leave it to them, trust what they tell you, and use the time saved to write the rest of the application.

Thanks to Nathaniel Golden (Nottingham Trent) and Jonathan Hollands (University of Nottingham) for invaluable comments on earlier versions of this article. Any errors that remain are my own.

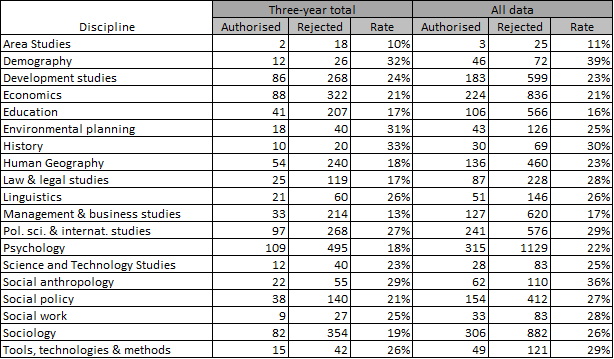

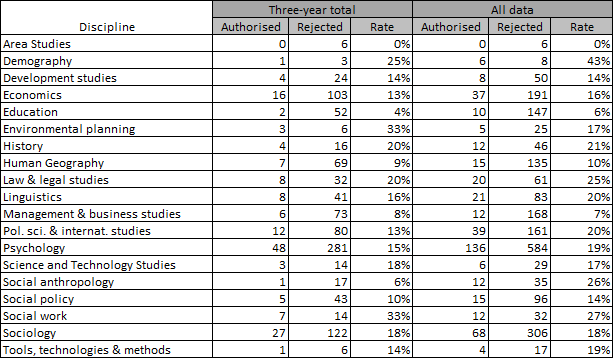

Post-doctoral or early career research fellowships in the social sciences have low success rates and are scarcely less competitive than academic posts. But if you have a strong proposal, at least some publications, realistic expectations and a plan B, applying for one of these schemes can be an opportunity to firm up your research ideas and make connections.

Post-doctoral or early career research fellowships in the social sciences have low success rates and are scarcely less competitive than academic posts. But if you have a strong proposal, at least some publications, realistic expectations and a plan B, applying for one of these schemes can be an opportunity to firm up your research ideas and make connections.