Times Higher Education recently published an interesting article by Donald Braben and endorsed by 36 eminent scholars including a number of nobel laureates. They criticise “today’s academic research management” and claim that as an unforeseen consequence, “exciting, imaginative, unpredictable research without thought of practical ends is stymied”. The article fires off somewhat scattergun criticism of the usual betes noire – the inherent conservatism of peer review; the impact agenda, and lack of funding for blue skies research; and grant application success rates.

I don’t deny that there’s a lot of truth in their criticisms… I think in terms of research policy and deciding how best to use limited resources… it’s all a bit more complicated than that.

Picking Winners and Funding Outsiders

Look, I love an underdog story as much as the next person. There’s an inherent appeal in the tale of the renegade scholar, the outsider, the researcher who rejects the smug, cosy consensus (held mainly by old white guys) and whose heterodox ideas – considered heretical nonsense by the establishment – are ultimately triumphantly vindicated. Who wouldn’t want to fund someone like that? Who wouldn’t want research funding to support the most radical, most heterodox, most risky, most amazing-if-true research? I think I previously characterised such researchers as a combination of Albert Einstein and Jimmy McNulty from ‘The Wire’, and it’s a really seductive picture. Perhaps this is part of the reason for the MMR fiasco.

The problem is that the most radical outsiders are functionally indistinguishable from cranks and charlatans. Are there many researchers with a more radical vision that the homeopathist, whose beliefs imply not only that much of modern medicine is misguided, but that so is our fundamental understanding of the physical laws of the universe? Or the anti-vaxxers? Or the holocaust deniers?

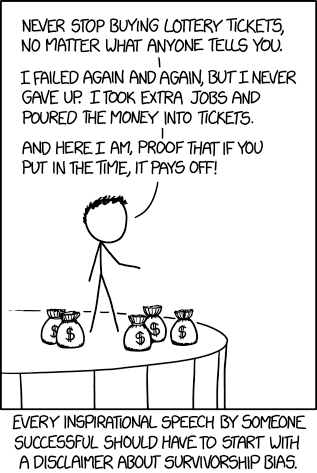

Of course, no-one is suggesting that these groups be funded, and, yes I’ll admit it’s a bit of a cheap shot aimed at a straw target. But even if we can reliably eliminate the cranks and the charlatans, we’ll still be left with a lot of fringe science. An accompanying THE article quotes Dudley Herschbach, joint winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize for Chemistry, as saying that his research was described as being at the “lunatic fringe” of chemistry. How can research funders tell the difference between lunatic ideas with promise (both interesting-if-true and interesting-even-if-not-true) and lunatic ideas that are just… lunatic. If it’s possible to pick winners, then great. But if not, it sounds a lot like buying lottery tickets and crossing your fingers. And once we’re into the business of having a greater deal of scrutiny in picking winners, we’re back into having peer review again.

One of the things that struck me about much of the history of science is that there are many stories of people who believe they are right – in spite of the scientific consensus and in spite of the state of the evidence available at the time – but who proceed anyway, heroically ignoring objections and evidence, until ultimately vindicated. We remember these people because they were ultimately proved right, or rather, their theories were ultimately proved to have more predictive power than those they replaced.

But I’ve often wondered about such people. They turned out to be right, but were they right because of some particular insight, or were they right because they were lucky in that their particular prejudice happened to line up with the actuality? Was it just that the stopped clock is right twice per day? Might their pig-headedness equally well have carried them along another (wrong) path entirely, leaving them to be forgotten as just another crank? And just because someone is right once, is there any particular reason to think that they’ll be right again? (Insert obligatory reference to Newton’s dabblings with alchemy here). Are there good reasons for thinking that the people who predicted the last economic crisis will also predict the next one?

A clear way in which luck – interestingly rebadged as ‘serendipity’ – is involved is through accidental discoveries. Researchers are looking at X when… oh look at Y, I wonder if Z… and before you know it, you have a great discovery which isn’t what you were after at all. Free packets of post-it notes all round. Or when ‘blue skies’ research which had no obvious practical application at the time becomes a key enabling technology or insight later on.

The problem is that all these stories of serendipity and of surprise impact and of radical outsider researchers are all examples of lotteries in which history only remembers the winning tickets. Through an act of serendipity, the XKCD published a cartoon illustrating this point nicely (see above) just as I was thinking about these issues.

But what history doesn’t tell us is how many lottery tickets research funding agencies have to buy in order to have those spectacular successes. And just as importantly, whether or not a ‘lottery ticket’ approach to research funding will ultimately yield a greater return on investment than a more ‘unimaginative’ approach to funding using the tired old processes of peer review undertaken by experts in the relevant field followed by prioritisation decisions taken by a panel of eminent scientists drawn from across the funder’s remit. And of course, great successes achieved through this method of having a great idea, having the greatness of the idea acknowledged by experts, and then carrying out the research is a much less compelling narrative or origin story, probably to the point of invisibility.

A mixed ecosystem of conventional and high risk-high reward funding streams

I think there would be broad agreement that the research funding landscape needs a mixture of funding methods and approaches. I don’t take Braben and his co-signatories to be calling for wholesale abandonment of peer review, of themed calls around particular issues, or even of the impact agenda. And while I’d defend all those things, I similarly recognise merit in high risk-high reward research funding, and in attempts by major funders to try to address the problem of peer review conservatism. But how do we achieve the right balance?

Braben acknowledges that “some agencies have created schemes to search for potentially seminal ideas that might break away from a rigorously imposed predictability” and we might include the European Research Council and the UK Economic and Social Research Council as examples of funders who’ve tried to do this, at least in some of their schemes. The ESRC in particular on one scheme abandoned traditional peer review for a Dragon’s Den style pitch-to-peers format, and the EPSRC is making increasing use of sandpits.

It’s interesting that Braben mentions British Petroleum’s Venture Research Initiative as a model for a UCL pilot aimed at supporting transformative discoveries. I’ll return to that pilot later, but he also mentions that the one project that scheme funded was later funded by an unnamed “international benefactor”, which I take to be a charity or private foundation or other philanthropic endeavor rather than a publically-funded research council or comparable organisation. I don’t think this is accidental – private companies have much more freedom to create blue skies research and innovation funding as long as the rest of the operation generates enough funding to pay the bills and enough of their lottery tickets end up winning to keep management happy. Similarly with private foundations with near total freedom to operate apart perhaps from charity rules.

But I would imagine that it’s much harder for publically-funded research councils to take these kinds of risks, especially during austerity. (“Sorry Minister, none of our numbers came up this year, but I’m sure we’ll do better next time.”) In a UK context, the Leverhulme Trust – a happy historical accident funded largely through dividend payments from its bequeathed shareholding in Unilever – seeks to differentiate itself from the research councils by styling itself as more open to risky and/or interdisciplinary research, and could perhaps develop further in this direction.

The scheme that Braben outlines is genuinely interesting. Internal only within UCL, very light touch application process mainly involving interviews/discussion, decisions taken by “one or two senior scientists appointed by the university” – not subject experts, I infer, as they’re the same people for each application. Over 50 applications since 2008 have so far led to one success. There’s no obligation to make an award to anyone, and they can fund more than one. It’s not entirely clear from this article where the applicant was – as Braben proposes for the kinds of schemes he calls for – “exempt from normal review procedures for at least 10 years. They should not be set targets either, and should be free to tackle any problem for as long as it takes”.

From the article I would infer that his project received external funding after 3 years, but I don’t want to pick holes in a scheme which is only partially outlined and which I don’t know any more about, so instead I’ll talk about Braben’s more general proposal, not the UCL scheme in particular.

It’s a lot of power in a very few hands to give out these awards, and represents a very large and very blank cheque. While the use of interviews and discussion cuts down on grant writing time, my worry is that a small panel and interview based decision making may open the door to unconscious bias, and greater successes for more accomplished social operators. Anyone who’s been on many interview panels will probably have experienced fellow panel members making heroic leaps of inference about candidates based on some deep intuition, and in the tendency of some people to want to appoint the more confident and self-assured interviewee ahead of a visibly more nervous but far better qualified and more experienced rival. I have similar worries about “sand pits” as a way of distributing research funding – do better social operators win out?

The proposal is for no normal review procedures, and for ten years in which to work, possibly longer. At Nottingham – as I’m sure at many other places – our nearest equivalent scheme is something like a strategic investment fund which can cover research as well as teaching and other innovations. (Here we stray into things I’m probably not supposed to talk about, so I’ll stop). But these are major investments, and there’s surely got to be some kind of accountability during decision-making processes and some sort of stop-go criteria or review mechanism during the project’s life cycle. I’d say that courage to start up some high risk, high reward research project has to be accompanied by the courage to shut it down too. And that’s hard, especially if livelihoods and professional reputations depend upon it – it’s a tough decision for those leading the work and for the funder too. But being open to the possibility of shutting down work implies a review process of some kind.

To be clear, I’m not saying let’s not have more high-risk high-reward curiosity driven research. By all means let’s consider alternative approaches to peer review and to decision making and to project reporting. But I think high risk/high reward schemes raise a lot of difficult questions, not least what the balance should be between lottery ticket projects and ‘building society savings account’ projects. We need to be aware of the ‘survivor bias’ illustrated by the XKCD cartoon above and be aware that serendipity and vindicated radical researchers are both lotteries in which we only see the winning tickets. We also need to think very carefully about fair selection and decision making processes, and the danger of too much power and too little accountability in too few hands.

It’s all about the money, money, money…

But ultimately the problem is that there are a lot more researchers and academics than there used to be, and their numbers – in many disciplines – is determined not by the amount of research funding available nor the size of the research challenges, but by the demand for their discipline from taught-course students. And as higher education has expanded hugely since the days in which most of Braben’s “500 major discoveries” there are just far more academics and researchers than there is funding to go around. And that’s especially true given recent “flat cash” settlements. I also suspect that the costs of research are now much higher than they used to be, given both the technology available and the technology required to push further at the boundaries of human understanding.

I think what’s probably needed is a mixed ecology of research funders and schemes. Probably publically funded research bodies are not best placed to fund risky research because of accountability issues, and perhaps this is a space in which private foundations, research funding charities, and universities themselves are better able to operate.