The Times Higher has a report on Sir Paul Nurse‘s ‘Anniversary Day’ address to the Royal Society. Although the Royal Society is a learned society in the natural rather than the social sciences, he makes an interesting distinction that seems to have – more or less unchallenged – become a piece of received wisdom across many if not all fields of research.

Here’s part of what Sir Paul had to say (my underline added)

Given this emphasis on the primacy of the individuals carrying out the research, decisions should be guided by the effectiveness of the researchers making the research proposal. The most useful criterion for effectiveness is immediate past progress. Those that have recently carried out high quality research are most likely to continue to do so. In coming to research funding decisions the objective is not to simply support those that write good quality grant proposals but those that will actually carry out good quality research. So more attention should be given to actual performance rather than planned activity. Obviously such an emphasis needs to be tempered for those who have only a limited recent past record, such as early career researchers or those with a break in their careers. In these cases making more use of face-to-face interviews can be very helpful in determining the quality of the researcher making the application.

I guess my first reaction to this is to wonder whether interviews are the best way of deciding research funding for early career researchers. Apart from the cost, inconvenience and potential equal opportunities issues of holding interviews, I wonder if they’re even a particularly good way of making decisions. When it comes to job interviews, I’ve seen many cases where interview performance seems to take undue priority over CV and experience. And if the argument is that sometimes the best researchers aren’t the best communicators (which is fair), it’s not clear to me how an interview will help.

My second reaction is to wonder about the right balance between funding excellent research and funding excellent researchers. And I think this is really the point that Sir Paul is making. But that’s a subject for another entry, another time. Coming soon!

My third reaction – and what this entry is about – is the increasingly common assumption that there is one tribe of researchers who can write outstanding applications, and another which actually does outstanding research. One really good expression of this can be found in a cartoon at the ever-excellent Research Counselling. Okay, so it’s only a cartoon, but it wouldn’t have made it there unless it was tapping into some deeper cultural assumptions. This article from the Times Higher back at the start of November speaks of ‘Dr Plods’ – for whom getting funding is an aim in itself – and ‘Dr Sparks’ – the ones who deserve it – and there seems to be little challenge from readers in the comments section below.

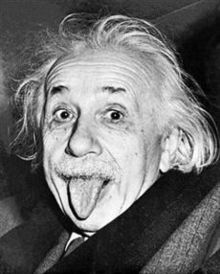

But does this assumption have any basis in fact? Are those who get funded mere journeymen and women researchers, mere average intellects, whose sole mark of distinction is their ability to toady effectively to remote and out-of-touch funding bodies? To spot the research priority flavour-of-the-month from the latest Delivery Plan, and cynically twist their research plans to match it? It’s a comforting thought for the increasingly large number of people who don’t get funding for their project. We’d all like to be the brilliant-but-eccentric-misunderstood-radical-unappreciated genius, who doesn’t play by the rules, cuts a few corners but gets the job done, and to hell with the pencil pushers at the DA’s office in city hall in RCUK’s offices in downtown Swindon. A weird kind of cross between Albert Einstein and Jimmy McNulty from ‘The Wire’.

While I don’t think anyone is seriously claiming that the Sparks-and-Plods picture should be taken literally, I’m not even sure how much truth there is in it as a parable or generalisation. For one thing, I don’t see how anyone could realistically Plod their way very far from priority to priority as they change and still have a convincing track record for all of them. I’m sure that a lot of deserving proposals don’t get funded, but I doubt very much that many undeserving proposals do get the green light. The brute fact is that there are more good ideas than there is money to spend on funding them, and the chances of that changing in the near future are pretty much zero. I think that’s one part of what’s powering this belief – if good stuff isn’t being funded, that must be because mediocre stuff is being funded. Right? Er, well…. probably not. I think the reality is that it’s the Sparks who get funded, but it’s those Sparks who are better able to communicate their ideas and make a convincing case for fit with funders’ or scheme priorities. Plods, and their ‘incremental’ research (a term that damns with faint praise in some ESRC referee’s reports that I’ve seen) shouldn’t even be applying to the ESRC – or at least not to the standard Research Grants scheme.

A share of this Sparks/Plods view is probably caused by the impact agenda. If impact is hard for the social sciences, it’s at least ten times as hard for basic research in many of the natural sciences. I can understand why people don’t like the impact agenda, and I can understand why people are hostile. However, I’ve always understood the impact agenda as far as research funding applications are concerned is that if a project has the potential for impact, it ought to, and there ought to be a good, solid, thought through, realistic, and defensible plan for bringing it about. If there genuinely is no impact, argue the case in the impact statement. Consider this, from the RCUK impact FAQ.

How do Pathways to Impact affect funding decisions within the peer review process?

The primary criterion within the peer review process for all Research Councils is excellent research. This has always been the case and remains unchanged. As such, problematic research with an excellent Pathways to Impact will not be funded. There are a number of other criteria that are assessed within research proposals, and Pathways to Impact is now one of those (along with e.g. management of the research and academic beneficiaries).

Of course, how this plays out in practice is another matter, but every indication I’ve had from the ESRC is that this is taken very seriously. Research excellence comes first. Impact (and other factors) second. These may end up being used in tie-breakers, but if it’s not excellent, it won’t get funded. Things may be different at the other Research Councils that I know less about, especially the EPSRC which is repositioning itself as a sponsor of research, and is busy dividing and subdividing and prioritising research areas for expansion or contraction in funding terms.

It’s worth recalling that it’s academics who make decisions on funding. It’s not Suits in Swindon. It’s academics. Your peers. I’d be willing to take seriously arguments that the form of peer review that we have can lead to conservatism and caution in funding decisions. But I find it much harder to accept the argument that senior academics – researchers and achievers in their own right – are funding projects of mediocre quality but good impact stories ahead of genuinely innovative, ground-breaking research which could drive the relevant discipline forward.

But I guess my message to anyone reading this who considers herself to be more of a ‘Doctor Spark’ who is losing out to ‘Doctor Plod’ is to point out that it’s easier for Sparky to do what Ploddy does well than vice versa. Ploddy will never match your genius, but you can get the help of academic colleagues and your friendly neighbourhood research officer – some of whom are uber-Plods, which in at least some cases is a large part of the reason why they’re doing their job rather than yours.

Want funding? Maximise your chances of getting it. Want to win? Learn the rules of the game and play it better. Might your impact plan be holding you back? Take advantage of any support that your institution offers you – and if it does, be aware of the advantage that this gives you. Might your problem be the art of grant writing? Communicating your ideas to a non-specialised audience? To reviewers and panel members from a cognate discipline? To a referee not from your precise area? Take advice. Get others to read it. Take their impressions and even their misunderstandings seriously.

Or you could write an application with little consideration for impact, with little concern for clarity of expression or the likely audience, and then if you’re unsuccessful, you can console yourself with the thought that it’s the system, not you, that’s at fault.