Last week Recently, I attended an Open Forum Events one day conference with the slightly confusing title ‘Research Impact: Strengthening the Excellence Framework‘ and gave a short presentation with the same title as this blog post. It was a very interesting event with some great speakers (and me), and I was lucky enough to meet up with quite a few people I only previously ‘knew’ through Twitter. I’d absolutely endorse Sarah Hayes‘ blogpost for Research Whisperer about the benefits of social media for networking for introverts.

Oh, and if you’re an academic looking for something approaching a straightforward explanation about the REF, can I recommend Charlotte Mathieson‘s excellent blog post. For those of you after in-depth half-baked REF policy stuff, read on…

I was really pleased with how the talk went – it’s one thing writing up summaries and knee-jerk analyses for a mixed audience of semi-engaged academics and research development professionals, but it’s quite another giving a REF-related talk to a room full of REF experts. It was based in part on a previous post I’ve written on portability but my views (and what we know about the REF) has moved on since then, so I thought I’d have a go at summarising the key points.

I started by briefly outlining the problem and the proposed interim arrangements before looking at the key principles that needed to form part of any settled solution on portability for the REF after next.

Why non-portability? What’s the problem?

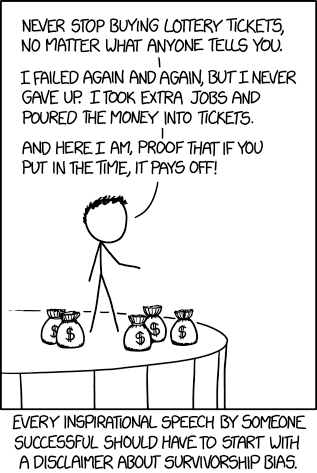

I addressed most of this in my previous post, but I think the key problem is that it turns what ought to be something like a football league season into an Olympic event. With a league system, the winner is whoever earns the most points over a long, drawn out season. Three points is three points, whatever stage of the season it comes in. With Olympic events, it’s all about peaking at the right time during the cycle – and in some events within the right ten seconds of that cycle. Both are valid as sporting competition formats, but for me, Clive the REF should be more like a league season than to see who can peak best on census day. And that’s what the previous REF rules encourages – fractional short term appointments around the census date; bulking out the submission then letting people go afterwards; rent-seeking behaviour from some academics holding their institution to ransom; poaching and instability, transfer window effects on mobility; and panic buying.

If the point of the REF is to reward sustained excellence over the previous REF cycle with funding to institutions to support research over the next REF cycle, surely it’s a “league season” model we should be looking at, not an Olympic model. The problem with portability is that it’s all about who each unit of assessment has under contract and able to return at the time, even if that’s not a fair reflection of their average over the REF cycle. So if a world class researcher moves six months before the REF census date, her new institution would get REF credit for all of her work over the last REF cycle, and the one which actually paid her salary would get nothing in REF terms. Strictly speaking, this isn’t a problem of publication portability, it’s a problem of publication non-retention. Of which more later.

I summarised what’s being proposed as regards portability as a transition measure in my ‘Initial Reactions‘ post, but briefly by far most likely outcome for this REF is one that retains full portability and full retention. In other words, when someone moves institution, she takes her publications with her and leaves them behind. I’m going to follow Phil Ward of Fundermentals and call these Schrodinger’s Publications, but as HEFCE point out, plenty of publications were returned multiple times by multiple institutions in the last REF, as each co-author could return it for her institution. It would be interesting to see what proportion of publications were returned multiple times, and what the record is for the number of times that a single publication has been submitted.

Researcher Mobility is a Good Thing

Marie Curie and Mr Spock have more in common than radiation-related deaths – they’re both examples of success through researcher mobility. And researcher mobility is important – it spreads ideas and methods, allows critical masses of expertise to be formed. And researchers are human too, and are likely to need to relocate for personal reasons, are entitled to seek better paid work and better conditions, and might – like any other employee – just benefit from a change of scene.

For all these reasons, future portability rules need to treat mobility as positive, and as a human right. We need to minimise ‘transfer window’ effects that force movement into specific stages of the REF cycle – although it’s worth noting that plenty of other professions have transfer windows – teachers, junior doctors (I think), footballers, and probably others too.

And for this reason, and for reasons of fairness, publications from staff who have departed need to be assessed in exactly the same way as publications from staff who are still employed by the returning UoA. Certainly no UoA should be marked down or regarded as living on past glories for returning as much of the work of former colleagues as they see fit.

Render unto Caesar

Institutions are entitled to a fair return on investment in terms of research, though as I mentioned earlier, it’s not portability that’s the problem here so much as non-retention. As Fantasy REF Manager I’m not that bothered by someone else submitting some of my departed star player’s work written on my £££, but I’m very much bothered if I can’t get any credit for it. Universities are given funding on the basis of their research performance as evaluated through the previous REF cycle to support their ongoing endeavors in the next one. This is a really strong argument for publication retention, and it seems to me to be the same argument that underpins impact being retained by the institution.

However, there is a problem which I didn’t properly appreciate in my previous writings on this. It’s the investment/divestment asymmetry issue, as absolutely no-one except me is calling it. It’s an issue not for the likely interim solution, but for the kind of full non-portability system we might have for the REF after next.

In my previous post I imagined a Fantasy REF Manager operating largely a one-in, one-out policy – thus I didn’t need new appointee’s publications because I got to keep their predecessors. And provided that staff mobility was largely one-in, one-out, that’s fine. But it’s less straightforward if it’s not. At the moment the University of Nottingham is looking to invest in a lot of new posts around specific areas (“beacons”) of research strength – really inspiring projects, such as the new Rights Lab which aims to help end modern slavery. And I’m sure plenty of other institutions have similar plans to create or expand areas of critical mass.

Imagine a scenario where I as Fantasy REF Manager decide to sack a load of people immediately prior to the REF census date. Under the proposed rules I get to return all of their publications and I can have all of the income associated for the duration of the next REF cycle – perhaps seven years funding. On the other hand, if I choose to invest in extra posts that don’t merely replace departed staff, it could be a very long time before I see any return, via REF funding at least. It’s not just that I can’t return their publications that appeared before I recruited them, it’s that the consequences of not being able to return a full REF cycle’s worth of publications will have funding implications for the whole of the next REF cycle. The no-REF-disincentive-to-divest and long-lead-time-for-REF-reward-for-investment looks lopsided and problematic.

I’m a smart Fantasy REF Manager, it means I’ll save up my redundancy axe wielding (at worst) or recruitment freeze (at best) for the end of the REF cycle, and I’ll be looking to invest only right at the beginning of the REF cycle. I’ve no idea what the net effect of all this will be repeated across the sector, but it looks to me as if non-portability just creates new transfer windows and feast and famine around recruitment. And I’d be very worried if universities end up delaying or cancelling or scaling back major strategic research investments because of a lack of REF recognition in terms of new funding.

Looking forward: A settled portability policy

A few years back, HEFCE issued some guidance about Open Access and its place in the coming REF. They did this more or less ‘without prejudice’ to any other aspect of the REF – essentially, whatever the rest of the REF looks like, these will be the open access rules. And once we’ve settled the portability rules for this time (almost certainly using the Schrodinger’s publications model), I’d like to see them issue some similar ‘without prejudice’ guidelines for the following REF.

I think it’s generally agreed that the more complicated but more accurate model that would allow limited portability and full retention can’t be implemented at such short notice. But perhaps something similar could work with adequate notice and warning for institutions to get the right systems in place, which was essentially the point of the OA announcement.

I don’t think a full non-portability full-retention system as currently envisaged could work without some finessing, and every bid of finessing for fairness comes at the cost of complication. As well as the investment-divestment asymmetry problem outlined above, there are other issues too.

The academic ‘precariat’ – those on fixed term/teaching only/fractional/sessional contracts need special rules. An institution employing someone to teach one module with no research allocation surely shouldn’t be allowed to return that person’s publications. One option would be to say something like ‘teaching only’ = full portability, no retention; and ‘fixed term with research allocation’ = the Schrodinger system of publications being retained and being portable. Granted this opens the door to other games to be played (perhaps turning down a permanent contract to retain portability?) but I don’t think these are as serious as current games, and I’m sure could be finessed.

While I argued previously that career young researchers had more to gain than to lose from a system whereby appointments are made more on potential rather than track record, the fact that so many are as concerned as they are means that there needs to be some sort of reassurance or allowance for those not in permanent roles.

Disorder at the border. What happens about publications written on Old Institution’s Time, but eventually published under New Institution’s affiliation? We can also easily imagine publication filibustering whereby researchers delay publication to maximise their position in the job market. Not only are delays in publication bad for science, but there’s also the potential for inappropriate pressure to be applied by institutions to hold something back/rush something out. It could easily put researchers in an impossible position, and has the potential to poison relationships with previous employers and with new ones. Add in the possible effects of multiple job moves on multi-author publications and this gets messy very quickly.

One possible response to this would be to allow a portability/retention window that goes two ways – so my previous institution could still return my work published (or accepted) up to (say) a year after my official leave date. Of course, this creates a lot of admin, but it’s entirely up to my former institution whether it thinks that it’s worth tracking my publications once I’ve gone.

What about retired staff? As far as I can see there’s nothing in any documents about the status of the publications of retired staff either in this REF or in any future plans. The logic should be that they’re returnable in the same way as those of any other researcher who has left during the REF period. Otherwise we’ll end up with pressure to say on and perhaps other kinds of odd incentives not to appoint people who retire before the end of a REF cycle.

One final suggestion…

One further half-serious suggestion… if we really object to game playing, perhaps the only fair to properly reward excellent research and impact and to minimise game playing is to keep the exact rules of REF a secret for as long as possible in each cycle. Forcing institutions just to focus on “doing good stuff” and worrying less about gaming the REF.

- If you’re really interested, you can download a copy of my presentation … but if you weren’t there, you’ll just have to wonder about the blank page…