A version of this article first appeared in Funding Insight in February 2019 and is reproduced with kind permission of Research Professional. For more articles like this, visit www.researchprofessional.com

You are the academic expert, in the process of applying for funding to make a major advance in your field. I am not. I am a Research Development Manager – perhaps I have a PhD or MPhil in a cognate or entirely different field, or nothing postgraduate at all. How can I possibly help you?

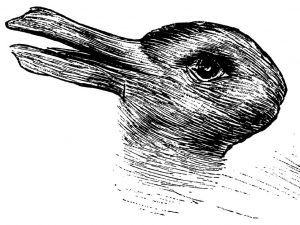

The answer lies in this difference of experience and perspective. Sure, we may look at the same things, but different levels of knowledge,understanding – as well as different background assumptions – mean we find very different meanings in them. We all look at the world through lenses tinted by our own experiences and expectations, and if we didn’t, we couldn’t make sense of it.

Interpreting funding calls

When academics look at funding calls, they notice and emphasise the elements of the call that suit their agenda and often downplay or fail to notice other elements. Early in my career I was baffled as to why a very senior professor thought that a funding call was appropriate for a project. He’s smarter than me, more experienced…so obviously I assumed I’d got it wrong. I went back to the call expecting to find my mistake and find that his interpretation was correct. But no…my instinct was right.

Since then I’ve regularly had these conversations and pointed out that an idea would need crowbarring to death to fit a particular call, and even then would be uncompetitive. I’ve had to point out basic eligibility problems that have escaped the finely-honed research skills of frightening bright people.

When research development professionals like me look at a funding call, we see it through tinted glasses too, but these are tinted by comparable calls that we’ve seen before. We see what has unusual or disproportionate emphasis or lack of emphasis, or even the significance of what’s missing. We know what we’re looking for and whereabouts in the call we expect to see it. Our reading of calls is enhanced by a deep knowledge of the funder and its priorities, and what might be the motivation or source of funding behind a particular call.

Of course, some academics have an excellent understanding of particular funders. Especially if they’ve received funding from them, or served on a panel or as a referee, or been invited to a scoping workshop to inform the design and remit of a funding call.

But if you’re not in that position, the chances are that your friendly neighbourhood research development professional can advise you on how to interpret any given funder or scheme, or put you in touch with someone who can.

We can help you identify the most appropriate scheme and call for what you want to do, and just as importantly, prevent you from wasting your time on bids that are a poor fit. Often the best thing I do on any given day is talking someone out of spending weeks writing an application that never had any realistic chance of success.

Reading draft applications

You must have internal expert peer review and encourage your academic colleagues to be brave enough to criticise your ideas and point out weaknesses in their iteration. Don’t be Gollum.

Research Development professionals can’t usually offer expert review, but a form of lay review can be just as useful. We may not be experts in your area, but we’ve seen lots and lots of grant applications, good and bad. We have a sense of what works. We know when the balance is wrong. We know when we don’t understand sections that we think we should be able to understand, such as the lay summary. We notice when the significance or unique contribution is not clearly spelled out. We know when the methods are asserted, rather than defended. We know when sections are vague or undercooked, or fudged. Or inconsistent. When research questions appear, disappear, or mutate during the course of an application.

When I meet with academics and they explain their project, I often find there’s a mismatch between what I understood from reading a draft proposal and what they actually meant. It’s very common for only 75%-90% of an idea to be on the page. The rest will be in the mind of the applicant, who will think the missing elements are present in the document because they can’t help but read the draft through the lens of their complete idea.

If your research development colleagues misunderstand or misread your application, it may be because they lack the background, but it’s more likely that what you’ve written isn’t clear enough. There’s a lot to be learned from creative misinterpretation.

None of this is a criticism of academics; it’s true for everyone. We all see our own writing through the prism of what we intend to write, not what we’ve actually written. It’s why this article would be even worse without Research Professional’s editorial team.