I’ve recently moved from a role supporting the Business School and the School of Economics to a central role at the University of Nottingham, looking after our engagement with research charities. I’m going from a role where I know a few corners of the university very well to a role where I’m going to have to get to know more about much more of it.

My academic background (such as it is) is in political philosophy and for most of my research development career I’ve been supporting (broadly) social sciences, with a few outliers. I’m now trying to develop my understanding of academic disciplines that I have little background or experience in – medical research, life sciences, physics, biochemistry etc. I suspect the answer is just time, practice, familiarity, confidence (and Wikipedia), but I found myself wondering if there are any short cuts or particularly good resources to speed things up.

Fortunately, if you’re a member of ARMA, you’re never on your own, and I sent an email around the Research Development Special Interest Group email list, with a promise (a) to write up contributions as a blog post and (b) to add some hints and tips of my own, especially for the social sciences.

So here goes… the collated and collected wisdom of the SIG… bookmark this post and revisit it if your remit changes…

Don’t panic… and focus on what you can do

In my original email, the first requirement I suggested was ‘time’, and that’s been echoed in a lot of the responses. “Time, practice, familiarity, confidence (and Wikipedia)” as Chris Hewson puts it. It’s easy to be overwhelmed by a sea of new faces and names and an alphabet soup of new acronyms- and to regard other people’s hard-won institutional/school/faculty knowledge as some kind of magical superpower.

Lorna Wilson suggests that disciplinary differences are overrated and “sometimes the narrative of ‘difference’ is what makes things harder. The skills and expertise we have as research development professionals are transferable across the board, and I think that the silos of disciplines led to a silo-ing of roles (especially in larger universities). With the changes in the external landscape and push with more challenge-led interdisciplinary projects, the silos of disciplines AND of roles I think is eroding.”

But there are differences in practices and norms – there are differences in terminology, outlook, career structures, internal politics, norms, and budget sizes – and I’m working hard trying not to carry social science assumptions with me. Though perhaps I’m equally likely to be too hesitant to generalise from social science experience where it would be entirely appropriate to do so.

Rommany Jenkins has “moved from Arts and Humanities to Life Sciences” and thinks that while “the perception might be that it’s the harder direction to go in because of the complexity of the subject matter […] it’s probably easier because the culture is quite straightforward […] although there are differences between translational / clinical and basic, the principles of the PI lab and team are basically the same”. She thinks that perhaps “it’s more of a culture shock moving into Arts and Humanities, because people are all so independently minded and come at things from so many different directions and don’t fit neatly into the funding boxes. […] I know a lot of people just find it totally bizarre that you can ask a Prof in Arts what they need in terms of costings and they genuinely don’t know.”

Charlotte Johnson moved in the opposite direction, from science to arts. “The shortcut was trying to find commonalities in how the different disciplines think and prepare their research. Once you realise that an artist and a chemist would go about planning their research project very similarly, and they only start to diverge in the experimental/interpretation stage, it does actually make it all quite easy to understand“

Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg says that her contribution “tends to be not so much on the science front, but on the social and economic or policy and political implications of the work STEMM colleagues are doing and recommendations around impact and engagement or even interdisciplinary angles to enquiries for larger projects.”

My colleague Liz Humphreys makes a similar (and very reassuring) point about using the same “skills to assess any bid by not focusing on the technical things but focus on all the other usual things that a bid writer can strengthen”. A lay summary that doesn’t make any lay sense is an issue regardless of discipline, as is a summary that doesn’t summarise that’s more of an introduction. Getting good at reviewing research grants can transcend academic disciplines. “If someone can’t explain to me what they’re doing,” says Claire Edwards, “then it’s unlikely to convince reviewers or a panel.”

Kate Clift make a similar point: “When I am working in a discipline which is alien to me I tend to try and ground the proposed research in something which I do understand so I can appreciate the bigger picture, context etc. I will ask lots of ‘W’ questions – Why is it important? What do you want to do? Who is going to do it? Less illuminating to me in this situations is HOW they are going to do it”.

Roger Singleton Escofet makes the very sensible point that some subjects are very theoretical “where you will always struggle to understand what is being proposed”. I certainly found this with Economics – I could hope to try to understand what a proposed project did, but how it worked would always be beyond me. Reminds me a bit of this Armstrong and Miller sketch in which they demonstrate how not to do public engagement in theoretical physics.

Ann Onymous-Contributor says that “multidisciplinary projects are the best way to ease yourself into other disciplines and their own specific languages. My background is in social sciences but because of the projects I have worked on I have experience of, and familiarity with a range of arts and hard science disciplines and the languages they use. Broad, shallow knowledge accumulated on this basis can be very useful; sometimes specific disciplinary knowledge is less important than understanding connections between different disciplines, or the application of knowledge, which typically also tend to be the things which specialists miss.” I think this is a really good point – if we allow ourselves it include the other disciplines that we’ve supported as part of interdisciplinary bids, we may find we’ve more experience that we thought.

Finding the Shallow End, Producing your Cheat Sheet

Lorna Wilson suggests “[h]aving a basic understanding” of methodologies in different disciplines, “helps to demonstrate how [research questions] are answered and hypotheses evidenced, and I think breaks through some of the ‘difference’. What makes things slightly more difficult is also accessibility, in terms of language of disciplines, we could almost do with a cheat sheet in terms of terms!”

Richard Smith suggests identifying academics in the field who are effective and willing communicators “who appreciate the benefits and know the means of conveying approaches and fields to non-experts… and do it with enthusiasm”. Harry Moriarty’s experience has been that often ECRs and PhD students are a particularly good source – many are more willing to engage, and perhaps have more to benefit from our advice and support.

Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg suggests attending public lectures (rather than expert seminars) which will be aimed at the generalist, and notes that expert-novice conversations will benefit the academic expert in terms of practising explanations of complex topics to a generalist audience. I think we can all recognise academics who enjoy talking about their work to non-specialists and with a gift for explanations, and those who don’t, haven’t or both.

Other non-academic colleagues can help too, Richard argues – especially impact and public or business engagement staff working in that area, but also admin staff and School managers. Sanja Vlaisavljevic wanted to “understand how our various departments operate, not just in terms of subject-matter but the internal politics”. This is surely right – I’m sure we’re all aware of historical disagreements or clashes between powerful individuals or whole research groups/Schools that stand in the way of certain kinds of collaboration or joint working. Whether we work to try to erode these obstructions or navigate deftly around them, we need to know that they’re there.

Caroline Moss-Gibbons adds librarians to the list, citing their resource guides and access/role with the university repository. Claire Edwards observes that many research development staff have particular academic backgrounds that might be useful.

Don’t try to fake it till you make it

“Be open that you’re new to the area, but if they’re looking for funding they need to be able to explain their research to a non-specialist” says Jeremy Barraud.

I’ve always found that a full, frank, and even cheerful confession of a lack of knowledge is very effective. I often include a blank slide in presentations to illustrate what I don’t know. My experience is that admitting what I don’t know earns me a better hearing on matters that I do know about (as long as I do both together), but I’m aware that as a straight, white, middle aged, middle class male perhaps that’s easier for me to do. I’ve suspected for some time now that being male (and therefore less likely to be mistaken for an “administrator”) means I’m probably playing research development on easy mode. There’s an interesting project around EDI and research development that I’m probably not best placed to do.

While no-one is arguing for outright deception, I’ve heard it argued that frank admissions of ignorance about a particular topic area may make it harder to engage academic colleagues and to find out more. If academic colleagues make certain assumptions about background, perhaps try to live up to those with a bit of background reading. It’s easy to be written off and written out, which then makes it harder to learn later.

I always think half the battle is convincing academic colleagues that we’re on their side and the side of their research (rather than, say, motivated by university income targets or an easier life), and perhaps it’s easy to underestimate the importance of showing an interest and a willingness to learn. Asking intelligent, informed, interested lay questions of an expert – alongside demonstrating our own expertise in grant writing etc – is one way to build relationships. My own experience with my MPhil is that research can be a lonely business, and so an outsider showing interest and enthusiasm – rather than their eyes glazing over and disengaging – can be really heartening.

Kate Clift makes an important point about combining any admissions of relative ignorance with a stress on what she can do/does know/can contribute. “I’m always very upfront with people and say I don’t have an understanding of their research but I do understand how to craft a submission – that way everyone plays to their strengths. I can focus on structure and language and the academic can focus on scientific content.”

Find a niche, get involved, be visible

For Jeremy Barraud, that was being secretary for an ethics committee. In my early days with Economics, it was supporting the production of the newsletter and writing research summaries – even though it wasn’t technically part of my remit, it was a great way to get my name known, get to know people, and have a go at summarising Economics working papers.

Suzannah Laver is a research development manager in a Medical School, but has a background in project management and strategy rather than medicine or science. For her it was “just time” and getting involved “[a]ttending the PI meetings, away days, seminars, and arranging pitching events or networking events.” Mary Caspillo-Brewer adds project inception meetings and dissemination events to the list, and also suggests attending academic seminars and technical meetings (as does Roger Singleton Escofet), even if they’re aimed at academics. This is great in terms of visibility and in terms of evidence of commitment – sending a message that we’re interested and committed, even if we don’t always entirely understand.

Mark Smith suggests visiting research labs or clinics, however terrifying they may first appear. So far I’ve only met academics in their offices – I’m not sure I trust myself anywhere near a lab. I’m still half-convinced I’ll knock over the wrong rack of test tubes and trigger a zombie epidemic. But lab visits are perhaps something I could do more of in the future when I know people better. And as Mark says, taking an interest is key.

Do your homework

I’ve blogged before about the problems with the uses and abuses of successful applications, but Nat Golden is definitely onto something when he suggests reading successful applications to look at good practice and what the particular requirements of a funder are. Oh, and reading the guidance notes.

Roger Singleton Escofet (and others) have mentioned that the Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering produce useful reports that “may be technical but offer good overviews on topical issues across disciplines. Funders such as research councils or Wellcome may also be useful sources since funders tend to follow (or set) the emerging areas.” Hilary Noone also suggests looking to the funders for guidance – trying to “understand the funders real meaning (crucial for new programmes and calls where they themselves are not clear on what they are trying to achieve)”.

There’s a series of short ‘Bluffer’s Guide’ books which are somewhat dated, but potentially very useful. Bluff your way in Philosophy was on my undergraduate reading list. Bluff your way in Economics gave me an excellent grounding when my role changed, and explained (among many other things) the difference between exogenous and endogenous factors. When supporting a Geography application, I learned the difference between pluvial and fluvial flooding. These little things make a difference, and it’s probably the absence of that kind of basic ground for many disciplines that I’m now supporting that’s making me feel uneasy. In a good way.

Harry Moriarty argues that it’s more complicated than just reading Wikipedia – the work he supported “was necessarily at the cutting edge and considerably beyond the level that I could get to in a sensible order – I had to take the work and climb back through the Wikipedia pages in layers, and then, once I had some underpinning knowledge, go back through the same pages in light of my new understanding”.

Specific things to do

“Become an NIHR Public Reviewer”, says Jeremy Barraud. “It’s easy to sign up and they’re keen to get more reviewers. Being on the other side of the funding fence gives a real insight into how decisions are reached (and bolsters your professional reputation when speaking with researchers). “

I absolutely second this – I’ve been reviewing for NIHR for some time and just finished a four year term as a patient/public representative on a RfPB panel. I’d recommend doing this not just to gain experience of new research areas, but as a valuable public service that you as a research development professional can perform. If you’ve got experience of a health condition, using NHS services (as a patient or carer), and you’re not a healthcare professional or researcher, I’m sure they’d love to hear from you.

Being a research participant, argues Jeremy Barraud, is “professionally insightful and personally fulfilling. The more experience you have on research in all its different angles, the better your professional standing”. This is also something I’ve done – in many ways it’s hard not to get involved in research if you’re hanging around a university. I’m part of a study looking at running and knee problems, and I’ve recently been invited to participate in another study.

Bonhi Bhattacharya registered for a MOOC (Massively Open Online Courses) – an “Introduction to Ecology” – Bonhi is a mathematician by training – “and it was immensely helpful in getting a grounding in the subject, as well as a useful primer in terminology.“ It can be a bit of a time commitment, but they’re also fascinating – and as above, really shows willing. I wrote about my experience with a MOOC on behavioural economics in a post a few years ago. Bonhi also suggests reading academics’ papers – even if only the introduction and conclusion.

Resources

Subscribe to The Conversation, says Claire Edwards, it’s “a great source of academic content aimed at a non-specialist audience”. In a similar vein, Helen Walker recommends the Wellcome-funded website Mosaic which is “great for stories that give the bigger picture ‘around’ science/research – sometimes research journeys, sometimes stories showing the broader context of science-related research.” Both Mosaic and The Conversation have podcast companions. Recent Conversation podcast series have looked at the Indian elections and moon exploration.

I’m a huge fan of podcasts, and there are loads that can help with gaining a basic understanding of new academic areas – in addition to being interesting (and sometimes amusing).

- Thinking Allowed – Laurie Taylor (social sciences)

- The Infinite Monkey Cage; Brian Cox, Robin Ince and guests (sciences, and increasingly laboured jokes about Brian Cox’s hair)

- BBC documentaries – you’re spoiled for choice here (BBC World Service Documentaries; Seriously…; The Briefing Room; Analysis.

- Freakonomics; (Economics, very US-centric)

- Social Science Bites; (Shortish interviews with social scientists)

- Stuff you Should Know: (Lay introduction to topics from science to history, US-centric)

- Hidden Brain (US-centric, looks at human behaviour)

- On HE issues, Fast Track Impact and the WonkHe show.

A quick search of the BBC has identified four science podcasts I should think about listening to – The Science Hour, Discovery, and BBC Inside Science. Very open to other suggestions – please tweet me or let me know in the comments/via email.

A huge thank you to all contributors:

I’m very grateful to everyone for their comments. I’ve not been able to include everything everyone said, in the interests of avoiding duplication/repetition and in the interests of keeping this post to a manageable length.

I don’t think there’s any great secret to success in supporting a new discipline or working in research development in a new institution – it’s really a case of remembering and repeating the steps that worked last time. And hopefully this blog post will serve as a reminder to others, as it is doing to me.

- Jeremy Barraud is Deputy Director, Research Management and Administration, at the University of the Arts, London.

- Bonhi Bhattacharya is Research Development Manager at the University of Reading

- Mary Caspillo-Brewer is Research Coordinator at the Institute for Global Health, University College London

- Kate Clift is Research Development Manager at Loughborough University

- Anne Onymous-Contributor is something or other at the University of Redacted

- Claire Edwards is Research Bid Development Manager at the University of Surrey.

- Adam Forristal Golberg is Research Development Manager (Charities), at the University of Nottingham

- Nathanial Golden is Research Development Manager (ADHSS) at Nottingham Trent University

- Chris Hewson is Social Science Research Impact Manager at the University of York

- Liz Humphreys is Research Development Manager for Life Sciences, University of Nottingham

- Rommany Jenkins is Research Development Manager for Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham.

- Charlotte Johnson is Senior Research Development Manager, University of Reading

- Suzannah Laver is Research Development Manager at the University of Exeter Medical School

- Harry Moriarty is Research Accelerator Project Manager at the University of Nottingham.

- Caroline Moss-Gibbons is Parasol Librarian at the University of Gibraltar.

- Hilary Noone is Project Officer (REF Environment and NUCoREs0, at the University of Newcastle

- Roger Singleton Escofet is Research Strategy and Development Manager for the Faculty of Science, University of Warwick.

- Mark Smith is Programme Manager – The Bloomsbury SET, at the Royal Veterinary College

- Richard Smith is Research and Innovation Funding Manager, Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social sciences, Anglia Ruskin University.

- Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg is Researcher Development Manager (Strategy) at the University of Sydney.

- Sanja Vlaisavljevic is Enterprise Officer at Goldsmiths, University of London

- Helen Walker is Research and Innovation Officer at the University of Portsmouth

- Lorna Wilson is Head of Research Development, Durham University

A version of this article first appeared in

A version of this article first appeared in

My first nomination comes via a

My first nomination comes via a  My second nomination is Sergeant Wilson of ‘Dad’s Army’, played by

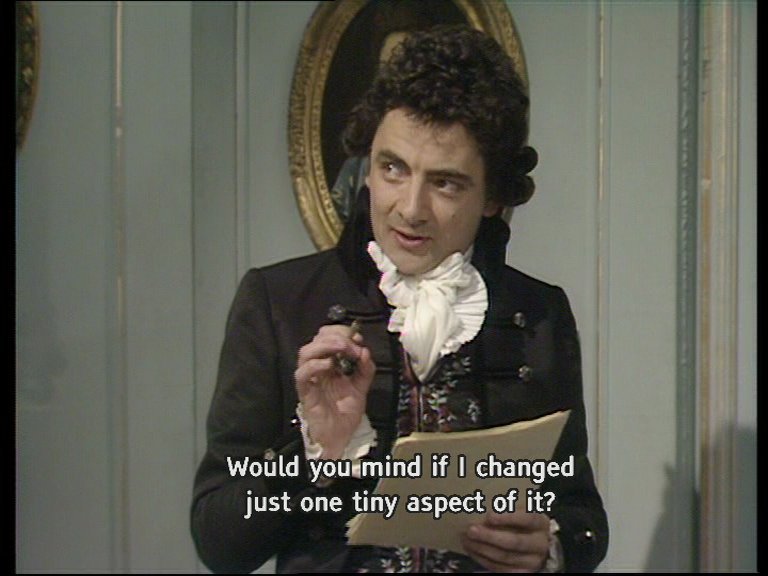

My second nomination is Sergeant Wilson of ‘Dad’s Army’, played by  My third – more controversially – is Edmund Blackadder, and in particular Blackadder III. This exchange alone – when reviewing the Prince of Wales’ first draft of a love letter – makes him the patron fictional saint of research development staff.

My third – more controversially – is Edmund Blackadder, and in particular Blackadder III. This exchange alone – when reviewing the Prince of Wales’ first draft of a love letter – makes him the patron fictional saint of research development staff. Next up, a trip to Fawlty Towers and Polly Sherman (Connie Booth, who also co-wrote the series), the voice of sanity (mostly) and a model of competence, dedication, and loyalty. She usually manages to keep her head while all around are losing theirs, and has a level of compassion, understanding, and tolerance for the eccentricities of those around her which the likes of Edmund Blackadder never reach.

Next up, a trip to Fawlty Towers and Polly Sherman (Connie Booth, who also co-wrote the series), the voice of sanity (mostly) and a model of competence, dedication, and loyalty. She usually manages to keep her head while all around are losing theirs, and has a level of compassion, understanding, and tolerance for the eccentricities of those around her which the likes of Edmund Blackadder never reach. Finally, one I’ve changed my mind over. Initially, it was Sir Humphrey Appleby (left), the Permanent Private Secretary in Yes (Prime) Minister, who was my nominee. While the Minister, Jim Hacker (centre), was all fresh ideas and act-without-thinking, Sir Humphrey was the voice of experience and the embodiment of institutional memory.

Finally, one I’ve changed my mind over. Initially, it was Sir Humphrey Appleby (left), the Permanent Private Secretary in Yes (Prime) Minister, who was my nominee. While the Minister, Jim Hacker (centre), was all fresh ideas and act-without-thinking, Sir Humphrey was the voice of experience and the embodiment of institutional memory.